This article is addressed to movement instructors but is also intended to be helpful to anyone seeking information about piriformis syndrome and sciatica.

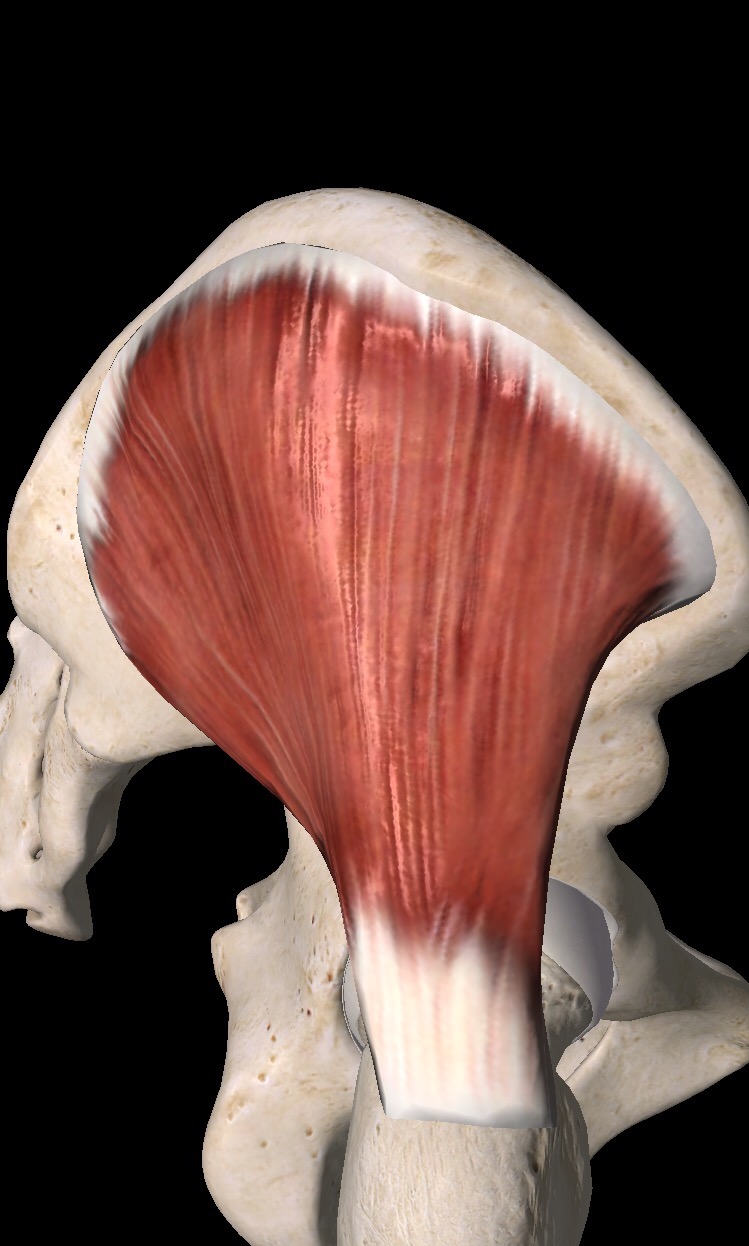

The piriformis is an important and sometimes elusive , deep external rotator of the hip.

The sciatic nerve runs either through , above or below this muscle. When the piriformis becomes over facilitated (hyper tonic) it irritates the sciatic nerve and may cause uncomfortable symptoms as well as weakness down the leg. This asymmetrical tone between the two legs can then lead to a variety of alignment issues both small and large. But the relationship between the piriformis and the sciatic nerve is not the only important pattern to observe.

Because of the piriformis’ central positioning and varying roles in the pelvis it can both inhibit or be inhibited by surrounding muscle groups. Therefore it is quite often a player is any dysfunctional patterns in the pelvis, hip and low back.

For the subject of this article I have chosen one of the more basic senarios . Since the piriformis is an external hip rotator if it is tight and short it will inhibit the ipsalateral (same side) internal rotators of the hip: the gluteus tmedius, gluteus minimus and Tensor Fascia Latea.

TFL (left) Gluteus Medius right)

To better understand how to affect the firing of the hip rotators let’s look at the action of going from deep hip flexion to neutral hip extension such as getting out of a chair unassisted or doing a squat.

When one is sitting in a chair the hips are flexed and the the sitbones are lengthened away from eachother. The action of standing up draws sitbones slightly together and the ASIS widen just a bit. But sometimes while moving from sitting to standing , one or both of the pelvic halves will travel too fast usually due to over engagement of the deep external rotators, especially the piriformis. This action can over mobilizing the SI, compress the sciatic nerve under a gripping piriformis or push the femurs too far forward in the hip causing pain or labral issues. If we know this dysfunctional pattern to be present we could repattern the movement at the sitbones to create a more open pelvic floor and less engagement from the piriformis. (These cues are really only appropriate for a “rotator gripper” and may not be useful for a healthy body as it could begin to inhibit the stabilizing properties of the deep rotators and pelvic floor. As always cueing must be appropriate to the individual )

The first way to assess this could be to watch a squat holding onto a push thru bar. Holding onto a doorknob (with the door closed!!) would suffice in the absence of Pilates equipment. Because the client is holding on they can sit way back, creating deep flexion. As the client descends into the squat cue them to widen their sitbones. This will start to encourage the length of the posterior hip muscles. After the area has been warmed up through this movement start to focus on the initiation out of the squat. You’ll want to only go to about a 90 degree squat. When the hip goes past 90 degrees the priformis goes from an external hip rotator to and internal hip rotator . With the chronic pelvic tucker/ but gripper you’ll want to cue them to keep their sitbones wide AS they press their heels into the floor and straighten their legs. Some times a well placed ball or thick yoga block between the inner thighs can help as long as the prop doesn’t promote a valgus (knock kneed ) alignment. If your client can integrate subtle cues ask them to visualize the thighs internally rotating as they straighten, or the inner thighs moving back. This cue won’t work for clients whom can only take commands literally as we are not looking to create actually internal rotation but only to turn on the internal rotators and inhibit the external rotators , mostly the piriformis.

***Quick note here. Being able to go to 90 of hip flexion with a neutral spine is a functional amount of flexibility. Encouraging much more than 90 degrees of hip flexion with a neutral pelvis could create an unwanted hyper mobility. Plus when the hip goes past 90 piriformis goes from an external hip rotator to and internal hip rotator.

If you look at the squat from the back you may notice that one sitbone appears more lateral than the other. A tight pelvic floor may not allow for a full expansion of the sitbones. This can be a good place to correct this asymmetry. Just make sure the hips are level so you are sure you are accurately assessing the tensions of the PF and not the low back.

Another important cue to incorporate is the femur sinking into the back of the hip during flexion. When the piriformis and surrounding musculature are very tight they doesn’t allow for the femur to have a full posterior glide.

The bottom line is to encourage balance around functional hip motions, keeping a good eye on discouraging external rotation as a initiating factor of movement as well as maintaining a neutral pelvis. Keep a look out for the next blog. Part 2 will discuss the relationship between the piriformis and the gluteus maximus.

![Piriformis Syndrome and Sciatica- Part 1 1 Piriformis-syndrome[1]](https://9mkkqfnsbx7d-u6436.pressidiumcdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Piriformis-syndrome1.png)